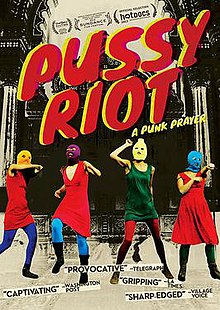

Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer

| Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Mike Lerner Maxim Pozdorovkin |

| Produced by | Mike Lerner Maxim Pozdorovkin Havana Marking |

| Starring | Nadezhda Tolokonnikova Maria Alyokhina Yekaterina Samutsevich |

| Cinematography | Antony Butts |

| Edited by | Simon Barker Esteban Uyarra |

| Music by | Simon Russell |

Production company | Roast Beef Productions |

| Distributed by | Goldcrest Films International |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 88 minutes[1] |

| Countries | Russia United Kingdom |

| Language | Russian |

Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer (Russian: Показательный процесс: История Pussy Riot, romanized: Pokazatel'nyy protsess: Istoriya Pussy Riot, lit. 'Show Trial: The Pussy Riot Story') is a 2013 documentary film by Mike Lerner and Maxim Pozdorovkin. The film follows the court cases on the Russian feminist/anti-Putinist punk-rock protest group Pussy Riot. Directed by Lerner and Pozdorovkin, the film featured publicly available footage of the court proceedings and interviews with the families of the band members, but no interviews with the band members themselves.[2]

The HBO network subsequently bought the U.S. television rights to the film[3][4] The film aired on HBO on 10 June 2013.

The BBC showed the film on 21 October 2013[5] in its Storyville series of documentaries. Reviews have generally been generally positive.[6]

Overview

[edit]On 21 February 2012, five members of the group staged a performance on the soleas of Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Savior.[7] Their actions were stopped by church security officials. By evening, they had turned it into a music video entitled "Punk Prayer – Mother of God, Chase Putin Away!".[8] The women said their protest was directed at the Orthodox Church leader's support for Putin during his election campaign.

On 3 March, two of the group members, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, were arrested and charged with hooliganism. A third member, Yekaterina Samutsevich, was arrested on 16 March. Denied bail, they were held in custody until their trial began in late July. On 17 August, the three members were convicted of hooliganism motivated by religious hatred, and each was sentenced to two years imprisonment.[9][10] Two other members of the group, who escaped arrest after February's protest, reportedly left Russia fearing prosecution.[citation needed] On 10 October, following an appeal, Samutsevich was freed on probation, her sentence suspended. The sentences of the other two women were upheld.[11] In late October, Alyokhina and Tolokonnikova were separated and sent to prison.[12]

The trial and sentence attracted considerable criticism,[13] particularly in the West. The case was adopted by human rights groups including Amnesty International, which designated the women prisoners of conscience, and by a wide range of musicians including Madonna, Sting, and Yoko Ono. Public opinion in Russia was generally less sympathetic towards the women.[14][15] Putin stated that the band had "undermined the moral foundations" of the nation and "got what they asked for".[16]

Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said he did not think the three members of Pussy Riot should have been sent to jail, but stressed that the release of the remaining two imprisoned members was a matter for the courts.[17][18][19]

Interviewees

[edit]- Nadezhda Tolokonnikova

- Maria Alyokhina

- Yekaterina Samutsevich

- Mark Feygin

- Nikolai Polozov

- Stanislav Samutsevich

- Andrey Tolokonnikov

- Peter Verzilov

- Violetta Volkova

- Natalia Alyokhina

Release

[edit]In January 2013, the film was released by British documentary filmmaking company Roast Beef Productions. The working title was Show Trial: The Story of Pussy Riot;[20] but was subsequently released as Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer. It debuted at the 2013 Sundance film festival, after which Pussy Riot's Yekaterina Samutsevich fielded questions from the audience via Skype. Among other things she reiterated that she had no intention of turning Pussy Riot into a commercial venture.[21] The film won a World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for "Punk Spirit" at the festival.[22]

In December 2013, the first screening in Russia was blocked by Department of Culture.[23]

The film was one of 15 feature-length documentaries short listed for a 2014 Academy Award,[24] but it was not included in the final list of nominees.[25]

Critical response

[edit]The film received generally reviews from critics.[26][27] On Metacritic it has a score of 72% based on reviews from 8 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[28] On Rotten Tomatoes it has an approval rating of 83% based on reviews from 34 critics, with an average rating of 6.9 out of 10.[6] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave it 4 out of 5 stars[29] and Amy Taubin of Film Comment called the film "A rousing portrait of courage and resilience."[30]

The film was one of 15 feature-length documentaries short listed for a 2014 Academy Award. It was not included in the final list of nominees.[24]

See also

[edit]- Pussy versus Putin, another 2013 Russian documentary about the group

References

[edit]- ^ "PUSSY RIOT – A PUNK PRAYER (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Justin Lowe (19 January 2013). "Pussy Riot – A Punk Prayer: Sundance Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Jay A. Fernandez (20 January 2013). "Sundance 2013: 'Pussy Riot' Doc to Air on HBO". Indiewire. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Jordan Hoffman (19 January 2013). "Sundance Review: Punk Rock Feminism and Orthodoxy Clash in 'Pussy Riot' Doc". film.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "BBC Four – Storyville, 2013-2014, Pussy Riot – A Punk Prayer". BBC. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ a b Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Pussy Riot gig at Christ the Savior Cathedral (original video). 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Панк-молебен "Богородица, Путина прогони" Pussy Riot в Храме ("Punk Prayer 'Mother of God, Chase Putin Away', Pussy Riot in the Cathedral")" (in Russian). 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Pussy Riot found guilty of hooliganism by Moscow court". BBC News. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Miriam Elder (17 August 2012). "Pussy Riot sentenced to two years in prison colony over anti-Putin protest". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Pussy Riot member Samutsevich sentence reduced to probation". RAPSI News. 10 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Bo Wilson (23 October 2012). "Pussy Riot Pair Separated and Sent to Gulags". The London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ According to BBC Monitoring, in the worldwide press there was 'almost universal condemnation' of the two-year sentence imposed on the three members of the group. "Press aghast at Pussy Riot verdict". BBC News. 18 August 2012. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Россияне о деле Pussy Riot ("Russians on the Pussy Riot case")" (in Russian). Levada. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Треть россиян верит в честный суд над Pussy Riot ("One-third of Russians believe in fairness of Pussy Riot trial")" (in Russian). Levada. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Putin deems fair Pussy Riot sentence". Interfax Religion. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Parfitt, Tom (2 November 2012). "Dmitry Medvedev says Pussy Riot should not be in prison". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ ""Медведев вновь не согласился с вердиктом Pussy Riot: я сажать бы не стал, посидели – и хватит" (Medvedev again disagrees with Pussy Riot verdict: says would not have sent them to jail, served enough time)" (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. 2 November 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

I wouldn't have sent them to jail if I had been the judge. I simply don't think that's right because these girls had already served a prison sentence. And actually that should have been enough. The fact that one has been released is fortunate ... but it's not up to me, rather to the courts and their lawyers. They have the right to appeal, and I think they should and let the courts consider the case on its own merits.

- ^ "Medvedev Calls for Pussy Riot Release". The Moscow Times. 6 November 2012. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ Geoffrey Macnab (21 November 2012). "Roast Beef to tell the story of Pussy Riot". screendaily.com. London: Screen International. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Katie Van Syckle (21 January 2013). "Pussy Riot Member Skypes at Sundance Premiere". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Sundance 2013: Festival Awards Announced". The Hollywood Reporter. 26 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (29 December 2013). "Russian screening of Pussy Riot film blocked by authorities", The New York Times.

- ^ a b Melena Ryzik (1 January 2014). "Banned at Home and Noticed by Oscars". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Nominees". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 16 January 2014.

- ^ Davies, Serena (22 October 2013). "Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer, BBC Four, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Dent, Grace (24 October 2013). "Grace Dent on TV: Storyville: Pussy Riot – a Punk Prayer, BBC4". The Independent. London. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ "Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer". Metacritic.

- ^ "Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer – review". The Guardian. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Fire and Ice". Film Comment. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer at IMDb

- Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer on HBO Archived 25 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer on BBC Four

- «Pussy Riot – A Punk Prayer» on Facebook

- Pussy Riot – The Doc on Twitter